War – Flight – Freedom

A foyer exhibition in connection with this year’s war memorial commemoration.

In the foyer, Alta Museum will exhibit several objects related to World War II from the 4th of November 2024 to the 4th of January 2026. This exhibition marks the fact that in 2024/25 80 years has passed since the evacuation of Alta and Finnmark in 1944 and the liberation of Finnmark and Norway in 1945.

The objects and texts in this exhibition are personal accounts that deal with the occupation, forced evacuation, scorched-earth policy, and reconstruction of Troms and Finnmark. They also include stories of people who have fled from war and conflict in more recent times. The material is drawn from Alta Museum’s online exhibition War – Flight – Freedom, which in turn is based on our cultural school project In the Luggage – Stories We Share.

In collaboration between Alta Museum, Alta Upper Secondary School, and the local community, students have collected stories from a neighbour, relative, or acquaintance. The starting point for the collection was an object that the person has a personal connection to and that relates to wartime experiences—whether the object was hidden and later rediscovered or brought along during evacuation and flight.

During Alta Museum’s one year long war memorial commemoration, several objects will be on display in our café. As part of this small exhibition, peace birds will also float from the ceiling. These peace birds, as we call them, have gone by several names, such as Lykkefuglen (the lucky bird) or Pomorduen (the Pomor dove). Many of them originate from the northernmost regions of the European part of Russia. The birds are made of two profiled wooden pieces joined in a cross shape, with wings and tail created by splitting the wood into thin shavings that spread out and interlock. Old stories from northern Russia tell that such birds hung from the ceilings of every Pomor home. The peace bird served as a lucky charm, believed to bring peace and prosperity to the household. During World War II, many Soviet prisoners of war were held in camps in Norway. As a token of gratitude for the food and help they received from the locals, they gifted them such birds.

Photograph top image: Ragnhildur Asvaldsdottir

Photograph list image: Kristin Nicolaysen

Drawing a War

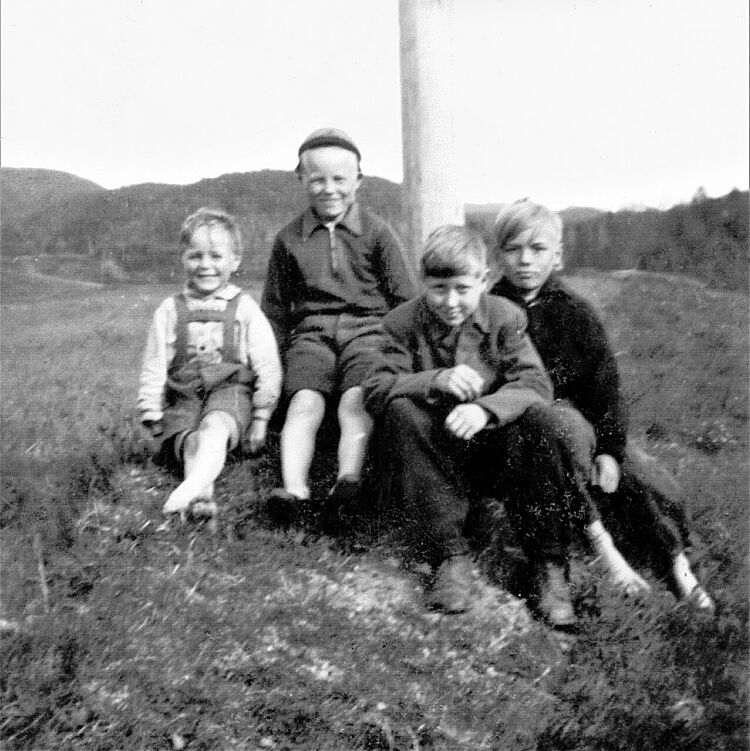

My great-uncle, Ole Samuel Kemi from Stjernøya, was five years old when the war broke out. The Germans' largest battleships, ‘Scharnhorst’ and ‘Tirpitz,’ passed through Stjernsund and into Altafjorden. Ole Samuel and his brothers found the war activities in the fjord so fascinating that they began drawing what was happening.

German soldiers manned a listening post on Stjernøya, and occasionally they would stop by to buy or demand milk. One time, they discovered the drawings and studied them with great interest. My great-grandmother became nervous, fearing they might interpret the drawings as documentation of the Germans’ positions in the fjord. When the soldiers asked where the boys had learned to draw like that, she replied that they certainly hadn't learned it from her. My uncle laughs heartily when he tells this story. There was a huge sense of relief when the soldiers left, but the very next day they returned. My great-grandmother and the boys were scared. The surprise was even greater when they had only come to give them crayons.

The next time the soldiers stood in the yard, it was not such a friendly visit. They brought matches and gasoline with them. The house and barn were to be burned, and all the livestock slaughtered. Forced evacuation was imminent. The Kemi family was evacuated by the boat ‘Gullberg’ to Tromsø, and then on to Mosjøen. Everything had been burned down by the time they returned. It must have been very tough, especially for my great-grandmother, says my uncle. She probably knew when they left that everything would be destroyed when they came back. My uncle and the other children didn't think about that. They were just small children, drawing a war.

Written by Katharina Wahl Nikolaisen

The Casket

During World War II, German soldiers occupied a bakery in Bossekop, Alta. As a 10-year-old, Mathis Sara was allowed to help the soldiers. They were delighted to have the young boy diligently helping in the bakery. He learned a bit of German, and the Germans picked up some Norwegian, allowing them to communicate and interact. Mathis received cakes and bread for his family.

Not far from the bakery there was a camp for Soviet prisoners of war. Mathis and his family smuggled food to the prisoners through the fence. However, they were caught, and Mathis’s father was threatened by a German soldier. With a pistol to his temple, he was ordered to stop. Despite this, Mathis took the risk and continued to give away food. He pretended to throw snowballs at trees and posts, but as soon as the German guards turned their backs and walked the other way, he quickly gave the food to the nearest prisoners. Some guards helped by deliberately turning their backs and allowing Mathis to feed the prisoners.

The Soviet prisoners were skilled craftsmen and made various items out of wood and aluminium. In the autumn of 1944, before the evacuation began, Mathis received an aluminium casket as a gift from one of them. For Mathis, the box is a cherished memory, which he keeps on display in his living room.

Written by Oxana Piskunova

The Teddy Bear That Saved Me

Sada has spent much of her life on the run. As a refugee from Iraq, she came to Norway, and this teddy bear, which Sada has owned since she was a baby, holds a special significance. It became unsafe in her home country when civil war broke out, and her family sought a safe place to live. After six years in Kurdistan-Turkey, their escape led Sada, on foot with human smugglers, through Turkey.

One of the scariest experiences was when she, her family, and thirty others travelled in a rubber boat from Turkey to Greece. Greek authorities stopped them at sea. They were shot at, and chaos erupted in the small boat. The authorities took them to a women’s and children’s prison in Greece, without her father. They were released and managed to board a cruise ship from Italy to Germany. With no cabin, they had to sleep on deck in cold weather. Then they took a train to Sweden, where they were denied asylum. The journey finally ended in Norway, where Sada now lives, grateful for the opportunity.

For Sada, it is hard to describe how she felt during the escape. The teddy bear was the only thing she had, a comfort she clung to, which also had a greater significance. Inside the bear, they hid their phone and passports. «This teddy bear is a symbol of everything I’ve been through. Sometimes it feels unreal to me. Everything we did was illegal, but we had no choice. My mum wanted to give us a chance to grow up and live a good life.»

Written by Serine Larsen.

The Harness

In 1944, the reindeer herders in Kautokeino were ordered to move their herds to Bassevuovdi Helligskogen in Troms. There, they were to slaughter the herd to feed the German soldiers, and then they were sent south. Some families did as they were told. However, most had ‘misunderstood’ the order and instead travelled to another Bassevuovdi - in Finland, managing to escape the Germans. The reindeer herders were not as desperate as many others. The reindeer provided food, milk, and clothing.

Many settled Sámi from Kautokeino joined the reindeer herding families during the autumn migration to Finland. But not all. My grandmother, who was twelve years old, and her family had a small herd and stayed in the autumn grazing area north of Kautokeino throughout the war. There, they had a turf hut near a good fishing lake. They would hide in the hut whenever they heard the sound of planes, and could only light fires when cooking. The reindeer bells had to be stuffed with moss to keep them silent.

The days passed slowly, and they had to find things to occupy their time. My grandmother’s father was skilled at making harnesses. He taught her how to fell birch trees, which were then carved to the correct length and thickness. My grandmother used her own knife to carve her own harness. In the spring, the news came that the war was over! When my grandmother fourteen years later, was to be married she used the harness that she had made on her own draught reindeer during the wedding procession. The harness is the only thing she has left from the days of the war, along with the memories of the horrors she experienced.

Written by Nils Ante Andersen Triumf

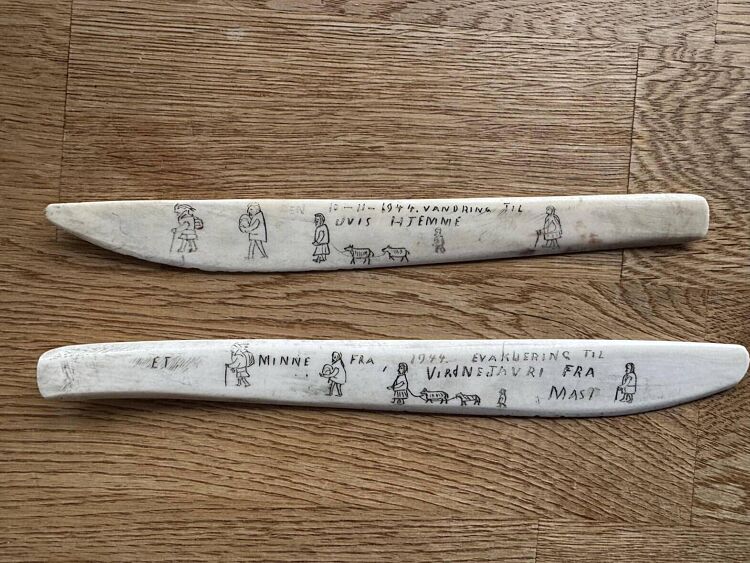

The Letter Opener – Breavaniibi: The Evacuation to Virdnejávri

The letter opener is a cherished memory for me, and its motif tells our story of when we received the evacuation order in 1944. We were ordered to gather at Nilsen Quay to evacuate southwards. My parents refused to follow the order and decided to flee up to the Finnmarksvidda from Gargia to Máze. I was six months old, and my sister Bjørg was seven. There were German soldiers in the area, and we had already been stopped once at a checkpoint in Kista, located in Gargia. A soldier emphasised the seriousness of the order by shooting Bjørg’s dog, Topsy, right in front of us.

Nevertheless, my parents stuck to their plan, and on a quiet night in November, we set off. Our horse, Fridtjof, pulled the long wagon loaded with supplies, while our cow, Stjerna, and our sheep, Lilja and Ulla, came along. All eight in our group took turns riding on the wagon to rest along the way – even Stjerna got a break. As soon as I was placed on the wagon, I started crying, so my godfather ended up carrying me the entire journey. Klemet N. Turi was our vappus – our guide across the plateau, while my grandmother, known as Stor-Hanna, stayed at the back of the group.

We were given shelter by the Olsen Hætta family in Lower Máze by Virdnejávri until peace came in 1945. They had a house with two rooms, and we were given one of them. Additionally, everyone made use of the lavvu at the settlement. Fortunately, the winter was mild. Klemet, our guide, made two letter openers. He gave one to me and one to Bjørg.

Written by Eva Synnøve Thomassen

The letters that never arrived

Towards the end of World War II, my great-grandfather, who was a German soldier, was ordered to leave Alta. He and my great-grandmother had fallen in love, and they had got a son, my grandfather who was nine months old then. Before my great-grandfather left, he wanted to give my great-grandmother a gift and a promise of love. There was a shortage of jewellery and goldsmiths, but in exchange for a combat ration pack, he had a thin, elegant gold ring exchanged for him. The ring had an engraving and had once meant something to someone else. My great-grandmother received the ring, and the two agreed that if she didn’t hear from him within two years, she should assume he was dead.

Two years passed, and she heard nothing. He had written letter after letter, but none reached her. They were intercepted by her parents, who were afraid of losing their daughter if she moved to Germany to be with him. Time went on, and she married another man and started a family. My great-grandfather, who had tried for so long to reach her, eventually moved on as well and started his own family. The gold ring was passed down to my great-grandmother’s granddaughter, my aunt, who today takes great care of the ring.

Written by Serine Larsen

The Most Precious Thing I Own

«I have a dream that one day there will be peace in Somalia, says Amina, reminiscing about the time before the war. I was the eldest child and my mother’s eager helper. I loved learning how to cook and going to the market with her. Since the civil war in 1991, everyday life was filled with fear. The most terrifying things happened at night—shooting, looting, and rapes. One evening, we heard gunshots and frantic banging on the door. Six young men stormed in, looking for money, gold, and food. My grandfather gave them his tusbax, his prayer beads, saying, «this is all I have. » They threw the beads to the ground, shattering them to pieces.

I was wearing a gold necklace that I had inherited from my grandmother. I hid the necklace under my tongue. They took almost everything we had. My grandmother and grandfather were left completely stripped of their clothes by the time the men were ready to leave. The last soldier stopped and grabbed my arm. «Don’t take my daughter!» my mother shouted. With the necklace in my mouth, I couldn’t speak to protest. One of the men said, «Leave the girl!» He let go of me, but it was so close. From that day, my escape was planned, though I didn’t know it at the time. My youngest brother and I were sent away with my aunt. For several years, we lived in a refugee camp near Kenya before we were granted UN refugee status and sent to Norway.

The gold necklace from my grandmother is the only thing I have left from my homeland, and it is the most precious thing I own.

Written by Kristin Nicolaysen

Take care of the blåbomma!

Gunnar Albert Iversen’s grandfather, Johan Edvart Iversen, was born in 1857. Johan was a Sea Sámi and lived as a fishing nomad, moving to where the fishing was good. He lived and fished at Vollan on Skjervøy, Rekvika on Arnøy, Svartvika on Måsøy, in Kvænangen, and on Årøya. In his boat, he kept a travel chest known as the Blåbomma. It contained kitchen supplies, flatbread, butter, and fishing hooks. The Blåbomma also had a small compartment, the bomma-leddik, which kept matches, fishing nets, sweets, and chewing tobacco extra dry.

In the summer of 1945, the war was over, and Gunnar had turned 14. He travelled with his family back home to Årøya. Everything had been burned—houses, farms, and boathouses. His grandfather Johan’s house at Fingernes on Isnestoften was the only one still standing. There, Gunnar’s mother found the chest - Blåbomma by the well next to the burnt-down boathouse, and the equipment inside was still intact!

When Johan died at the age of 83, his last words were: « I’m going to sail, but this time I won’t take the Blåbomma with me.» Gunnar inherited the Blåbomma, with his mother’s instruction: «Take care of the Blåbomma!» The Blåbomma you see here has been restored.

Written by Vilde Iren Mikalsen Strøm

You can read this and many other stories in Alta Museum's online exhibition War – Flight – Freedom, taken from our cultural school project programme In the Luggage – Stories We Share. This is a collaboration between Alta Museum, Alta Upper Secondary School, and the local community in Alta.

Krig, flukt og frihet | Alta Museum

Welcome to a memorable reflection on our war history!