The Northern Lights – from mythology to science in Alta

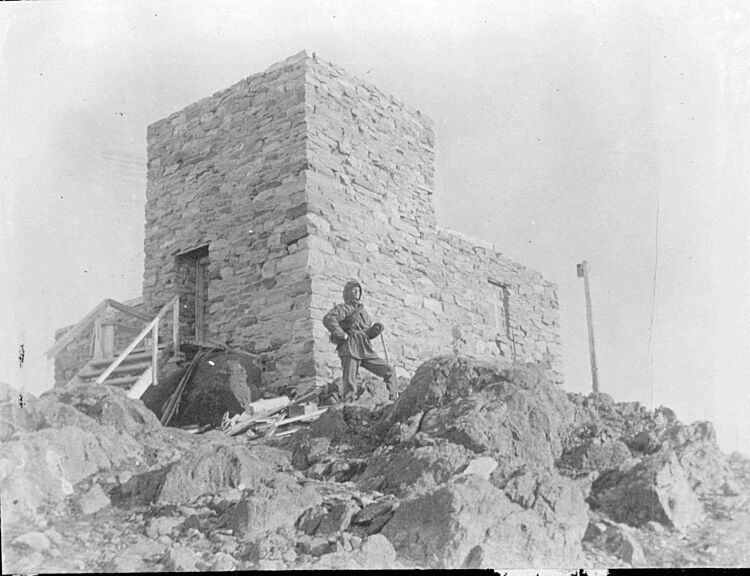

The world's first Northern Lights observatory was built on Mount Haldde in Alta, 900 m above sea level. The oldest of the observatory buildings was put into use in 1899. It was in active use until 1926 when its operation was transferred to Tromsø.

It was Professor Kristian Birkeland who had taken the initiative to realise the project, and the Norwegian parliament financed the running of it. But the fact that it was built right here was not only due to the fact that Alta is one best places to study the Northern Lights, but first and foremost because of the outstanding research carried out by the French Recherche expedition in Altafjord in 1838-1839. Their studies were the background for a number of Norwegian and foreign researchers coming to Alta in the 1800s to study one of the night sky's most beautiful and mysterious phenomena.

The Northern Lights observatory on Haldde was burnt down by the German forces of occupation in 1944. The photo shows the observatory after the restoration of the top building, Borgen, in 1983, and the new storage building (bottom) in 1986 before the roof and windows were added to the main building in 1989.

1838: An international expedition supported by the French king comes to Alta

The French Marine minister sent an international research team to Finmark and Spitsbergen. It was supported by King Louis Philippe who had been in Finmark in 1795. The expedition is called the Recherche Expedition after the accompanying ship "La Recherche," but is also known as the Gaimard Expedition after its leader, the marine doctor and zoologist, Paul Gaimard.

In August 1838 a group of researchers arrived to overwinter here and, amongst other things, study the Northern Lights. They had initially planned to establish a winter base in Hammerfest, but they heard that there was less cloud cover and fog in Altafjord, which would give better conditions for observations of the night sky. They rented accommodation in Madame Klerck's inn at Bossekop farm (later called Nielsen farm in north-east Bossekop towards Skaialuft). To aid their observations they were allowed to build three small log cabins close to the farmyard and on Lille-Berget (on the south side of Nielsenberget).

The beautiful illustrations of the Northern Lights phenomena made by the expedition's artist, Louis Bevalet, made Bossekop famous throughout the whole of Europe. According to the Northern Lights researcher Asgeir Brekke, the lithographs have "inspired many a keen traveller to experience the Northern Lights in their rightful element," based as they were on sketches that were "dashed off with frostbitten nails in the winter's night."

1830s and 40s: "The Scientific Society in Kåfjord" and its Northern Lights observations

In 1837 the English leadership of the copper works established "The Scientific Society in Kåfjord" with the mines engineer and later works director, Thomas as chairman. The society co-operated with the Recherche team and undertook to continue the expedition's Northern Lights records until 1844, and later for a further five years. These systematic observations over a period of several years were decisive in making Alta a centre of international research through the 1800s.

1882-83: International Polar Research Year with the Norwegian main station in Bossekop

Carl Weyprecht from Austria took the initiative in establishing the International Polar Research Year 1882-83. Twelve polar stations were set up throughout the northern hemisphere. The Norwegian head station was financed by the government and was to make observations of the Northern Lights. It was situated at Breverud farm in Bossekop, about 1 km from Bossekop farm. This location was chosen to aid comparisons with the results of the French 1838-39 expedition. It was led by Aksel Steen, otherwise deputy manager of the Norwegian Meteorological Institute.

The Danish-Norwegian scientist Sophus Tromholt accumulated the finances necessary to establish his own Northern Lights station in Kautokeino in co-operation with his "admirable friend Aksel Steen." Tromholt's scientific book "Under the rays of the Northern Lights" was also published and in English in the USA, and in German. It is not only a beautiful book; it is also well written. It begins with an eight-page long eulogy of Alta and especially the beauty of Bossekop. When he reaches the end of his praises of the glories of Alta he gets to the main point - the Northern Lights. "There are not many places that can rival Bossekop with regard to favourable conditions for observing the Northern Lights." The book and the many lectures he later held in America and Europe have contributed to making Bossekop world famous.

The oldest surviving photo of the Northern Lights – taken in Bossekop 5th January 1892

In 1838-39 the French team had to draw the Northern Lights by hand to show how they changed during the course of the winter night. Sophus Tromholt is regarded as the first person to have photographed the Northern Lights in 1885, but that was in Christiania (Oslo) of all places! He used an 8 minutes exposure. That photo has never been published. The oldest surviving published photo of the Northern Lights was taken in Bossekop on January 5th by the German Martin Brendel, who was a member of the German Northern Lights expedition. The exposure time for that photo was a mere 7 seconds.

1899-1903: Norway and Northern Lights research reach new heights on mountain tops around Alta

At the previous turn of the century, the time of the dissolution of the union with Sweden, one of the main concerns of the nascent Norway was to win worldwide respect by virtue of its heroic deeds. In August 1896 Fridtjof Nansen returned to Norway after being absent for three years in an attempt to reach the North Pole. The polar ship, Fram, was given a hero's welcome along the whole of the coast and Hansen was given a reception in Oslo which was more tumultuous that anyone else had ever received.

On the 2nd of February 1897, Kristian Birkeland, along with two assistants, journeyed from Christiania to Finnmark to find a mountaintop which could be a suitable site for Northern Lights calculations. But he had no intention of scouring the whole region to find one. He went straight to Alta and was at Gargia mountain lodge on the 8th of February.

That Kristian Birkeland wanted to move Northern Lights research to the tops of mountains was in keeping with the spirit of the age. His trip to the Alta district in February 1897 to find a suitable mountain site was highly dramatic. He almost died in the strong winds and 25 degrees of frost at Beskades. But in September that year, on a new reconnaissance trip, he found what the Northern Lights researcher, Asgeir Brekke, has called "Birkeland's Mecca and Medina."

In 1899 Professsor Birkeland persuaded Parliament to approve the building of observatories on Haldde (900 metres above sea level) and Talviktoppen. He himself overwintered on Haldde from the 19th to the 20th century. Sem Sæland, who was later to become the first president of the Norwegian Institute of Technology, was responsible for the observatory on Talviktoppen. Birkeland's academic paper on "The Norwegian aurora borealis expedition of 1899-1900" was published in French with the title page showing a drawing of Haldde and a "pure" Norwegian flag (without the union symbol) even though it was printed in 1901.

In 1902-03 Birkeland established a network of Northern Lights observatories in the northern regions with its centre in Kåfjord in Alta. Based on this research he published two large volumes in English which are classic masterpieces for researchers around the world.

1910-13: The altitude of the Northern Lights is accurately calculated at the Bosssekop research station

Many people think only of the mountain peak Haldde in connection with Northern Lights research in Alta. But it was in fact down by the fjord in Bossekop that it all began, and the research carried out there has a longer history. The Recherche team at Bossekop mapped out the expanse of the Northern Lights and indeed the atmosphere when, in 1838-39, they calculated that the Northern Lights phenomenon occurred between 90 and 150 km above the earth's surface. In the 1880s Tromholt calculated that the average height was 113 km, an incredibly accurate result. Professor Carl Størmer took thousands of photos in Alta in 1910 and 1913 to conclude that the average height was 110 km. He took photos of the Northern Lights simultaneously from two different stations, Alta Church in Bossekop and Øvre Alta school.

In the years 1912-15 Northern Lights researchers Lars Vegard and Ole Andreas Krogness followed up Størmer's work with a series of photos from a network of stations: Bossekop, Elvebakken, Gargia, Øksfjord and Alteidet, with Alta as the centre. In 1913, on behalf of Kristian Birkeland and the Northern Lights observatory, Lars Vegard bought a property in Bossekop which the researchers named "Aurora." In 1932 it was entrusted to "The Norwegian Institute for Cosmic Physics."

1912-26: Haldde – the world's first permanent Northern Lights observatory

In 1910 Birkeland persuaded the State authorities to grant the finance for the permanent running and expansion of the observatory on Haldde. He had argued that "a permanent observatory on Haldde would be a gold mine for scientific discoveries which would be significant for weather forecasting and thus be of practical benefit for the fisher folk of the far north."

A new building was erected in 1912 and expanded in 1913-15 so that there were four apartments provided for the researchers and their families. Norway was a pioneering country in meteorology and geophysics and Haldde became a stable workplace for some of Norway's and the world's leading researchers in these fields. Ole Andreas Krogness was appointed as manager and moved in with his family in 1912. Olaf Devik, who was responsible for improving "the weather forecast for northern Norway," had Haldde as his home base from 1915. The weather forecasts which they sent by telegram were very important for the fishermen and other people in the north of Norway. The last manager of Haldde, the Swede Hilding Köhler, was especially interested in the study of cloud formations over Haldde, and was a pioneer in ozone research. One of his major theses has the somewhat poetic title "On Water in the Clouds."

Köhler worked tirelessly for the cause of making the observatory an academy in Finnmark for the study of the natural sciences, but the Norwegian Parliament passed a resolution on 31st August 1926 to close down the activity on Haldde. The inspiring but hard life in the "knights' fortress" on the mountain top had come to an end. The new Northern Lights observatory in Tromsø was opened in 1928. After the Germans' burnt-earth destruction of Finnmark in 1944 there was nothing left after 80 years of Northern lights research in Bossekop, and only the solid stone walls remained standing until restoration work began in the 1980s.

In 2017 Alta municipality entered into an agreement with the Norwegian Tourist Association about renting the top and oldest building on Haldde, "the fortress." It's a 3-hour hike in summer to walk the 9 km from Kåfjord to the old observatory. The last 4 km are along the same track as the researchers used a hundred years ago.

The Northern Lights still light up the night sky over Alta. As early as the 1800s, research had shown that the Northern Lights occurred most frequently in a 500 km zone which was not closest to the magnetic North Pole but 2000 km away on the same latitude as the northern regions of Alaska, Canada and Siberia. Northern Norway is a region with the most "agreeable" climate in this zone. In this "mild land of the Northern Lights" Alta is one of the places blessed with the most clear night skies. This is why Sophus Tromholt could say in 1885 that "not many places can rival Bossekop with regards to favourable conditions for observing the Northern Lights."

(Sophus Tromholt 1885)

Written by Hans Christian Søborg

Read more:

Abrahamsen, Å.K. (1997). Nordkalottens første storindustri, kobberverket i Kåfjord, Alta. Fotefar mot nord. Alta: Finnmark fylkeskommune og Alta kommune.

Brekke, A. (1982). «Haldde - arnestedet for den moderne nordlysforskning». Altaboka. Årbok for Alta: 56-75. Alta: Alta historielag.

Brekke, A. (1985). «Haldde-observatoriet - verdas fyrste nordljosobservatorium». Været. Populærvitenskapelig tidsskrift. 1985 (nr. 2): 43-49. Oslo.

Brekke, A. og Egeland, A. (1979). Nordlyset. Fra mytologi til romforskning. Oslo: Grøndahl og Søn Forlag.

Brekke, A. og Hansen, T. L. (1997). «Nordlys, Vitenskap, Historie, Kultur». Alta. Alta Museums Småskrifter: Nr. 4.

Bunting, M. og Iversen, T. (2014). Nordlysfront. Hverdag og vitenskap 1898-1928. Stamsund: Orkana forlag.

Devik, O. (1972). Blant fiskere, forskere og andre folk. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Devik, O. (1976). Fra pionertiden i norsk fysikk og geofysikk. Med innledning om forfatteren og Haldde-observatoriet av O. Holt. Tromsø: Universitetet i Tromsø.

Holt, O. (1980). «Nordlysobservatoriet gjennom 50 år. Nordlysobservatoriet 50 år». Ottar Nr. 121-122: 43-61. Universitetet i Tromsø.

Jago, L. (2002). Nordlysets gåte. Beretningen om Kristian Birkeland. Pioneren som ofret alt i vitenskapens tjeneste. Oslo: Gyldendal.

Knutsen, N. M. og Posti, P. (2002). La Recherche. En ekspedisjon mot nord. Une expédition vers le Nord. Tromsø: Angelica forlag.

Krogness, O. (1982). «En rapport fra Haldde i 1915. Haldde-observatoriet, dets virksomhet og noen foreløpige resultater». Altaboka 1982, Årbok for Alta: 76-84. Alta: Alta historielag.

Nielsen, J. P. (1995). Altas historie. Bind 2. Det arktiske Italia (1826-1920). Alta: Alta kommune.

Nielssen, A.R. og Petterson, A. (1993). Nordlyspionerene. Menneskene og observatoriet på Halddetoppen i Alta. Oslo: Grøndahl og Dreyers Forlag.

Søborg, H.C. (2016). «Nordlysforskernes hytter, hus og borg i Bossekop, på Elvebakken og i Kåfjord». Altaboka 2016: 97-116. Alta: Alta historielag.

Tromholt, S. (1885). Under Nordlysets Straaler. København: Gyldendalske Boghandels Forlag.